As Russia and Iran have come under increasingly restrictive international economic sanctions, the two countries have turned to each other and similarly sanctioned states in a bid to develop trade that can circumvent the punitive measures.

Largely cut off from international banking systems, export markets, and foreign resources and technologies, they have strengthened their own trade relations while building economic ties with pariah states such as North Korea and Belarus, and others such as Venezuela and Burma that have been sanctioned by the United States and the European Union for human rights and other abuses.

But while such states might be willing to deal in a shared effort to counter the West, long-standing rivalries, logistical difficulties, and similarity of products greatly limit the effectiveness of any sort of bloc of the sanctioned, experts say.

“They’re geographically spread out. They don’t have things that they want to buy and sell from each other. And they don’t like each other,” said Peter Piatetsky, a former U.S. Treasury Department official who is now the CEO of the consultancy firm Castellum.AI. “It’s a terrible club to be in.”

Sanctions Upon Sanctions

Russia and Iran entered the year as the two most sanctioned countries in the world, and attempts to hold them to account for their internationally condemned actions in 2022 only compounded their problems.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February set the table for a raft of new sanctions targeting the country’s lucrative energy sector. Many Russian banks were also cut off from the world’s dominant financial transaction network, SWIFT, greatly inhibiting Moscow’s ability to conduct trade.

Iran, another major energy exporter, had hoped that existing sanctions over its controversial nuclear program would be dropped in negotiations to revive its stalled nuclear deal with global powers. Instead, the United States and the European Union imposed new sanctions on Tehran over its support for Russia’s war in Ukraine and its crackdown on antiestablishment protests at home.

They’re geographically spread out. They don’t have things that they want to buy and sell from each other. And they don’t like each other. It’s a terrible club to be in.”

— Peter Piatetsky, Castellum.AI

Even before the war in Ukraine began, Tehran and Moscow were envisioning the benefits of working out trade deals in an effort to circumvent sanctions.

“Both Iran and Russia are targeted by sanctions, and they can take advantage of this opportunity,” Iran’s Oil Ministry tweeted in January 2022 as officials met in Moscow to iron out areas of increased economic cooperation, including in the manufacturing and energy sectors.

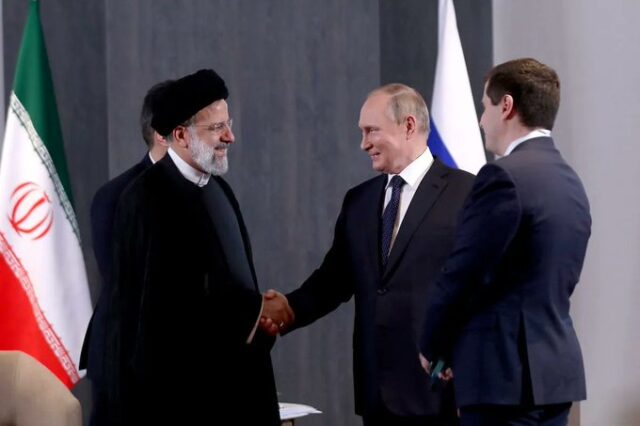

While hosting a Russian delegation in Tehran in November, Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi pledged to upgrade relations with Moscow to a “strategic” level, something he said is “the most decisive response to the policy of sanctions and destabilization of the United States and its allies.”

Others Enter The Ring

Other countries interested in challenging the West attracted attention from Moscow and Tehran, as well.

Belarus, itself under sanctions for its support for Russia’s war effort and its own crackdown on anti-government protests in 2020-21, saw the potential of inking fresh agreements this year with Moscow and Tehran that boosted trade with both.

Venezuela, which in the wake of its crackdown on protests in 2014 has been under U.S. and EU sanctions, struck a 20-year cooperation agreement with Tehran this year.

According to Benjamin Tsai, a former U.S. government intelligence officer who is now a senior associate with the risk intelligence firm TD International, in addition to Belarus and Venezuela, North Korea, Syria, and Burma (also known as Myanmar), “all play a role in trading with Russia or Iran.”

China, he said in written comments, “benefits from Russian and Iranian energy imports,” but is “playing a delicate balancing game of supporting Russia and Iran diplomatically and ideologically while not violating sanctions.” This is because, Tsai said, China “cannot afford to be cut off from the West.”

Ironically, Russia’s lowering of prices to boost exports to China was seen as harming Iran’s own efforts to sell its oil.

China and Russia did throw a bone to Iran in September when the two countries, which lead the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), formally agreed to make Iran a permanent member, paving the way for increased trade.

E-Trade And De-Dollarization

Sanctioned states, hindered by obstacles to international shipping and financial services, employ a number of different methods to conduct trade among themselves.

“They can engage in barter or trade that is not denominated in U.S. dollars,” wrote Tsai. “For example, Western sanctions have increased Russia’s use of the Chinese yuan to settle bilateral trade. Russian entities have also attempted to evade sanctions by using cryptocurrencies.”

Russia and Iran have long floated the idea of establishing alternative currencies to avoid dollar-denominated trade.

Since it came under sanctions for its seizure of Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and backing for pro-Russia separatists in eastern Ukraine in 2014, Russia has attempted to expand the use of its own banking system to replace SWIFT.

This year, Russia found a willing partner in Iran, which has claimed to have completed import deals using an unspecified cryptocurrency. The two states took steps to trade in their respective national currencies and worked to integrate their homegrown electronic banking payment systems — Mir and Shetab, respectively — as part of their de-dollarization push.

When Iran and Russia did not succeed in direct trade with sanctioned states, they turned to exchanges of military goods, technology, or know-how.

The United States has accused North Korea of supplying munitions to Russia to replenish stocks that were depleted due to the fighting in Ukraine. Iran, meanwhile, has supplied combat and “kamikaze” drones to be used on the battlefield in Ukraine, while Britain has accused Russia of paying Iran back by supplying it with “advanced military components.”

Such workarounds aside, however, Piatetsky said Iran, Russia, and other sanctioned states lack tradable commodities that they do not already export themselves.

“There’s essentially this problem where yes, you can do business with each other, but you don’t really have anything the other one wants,” Piatetsky said.

Russia, Iran, and Belarus are all energy producers, and with Russia’s increased sales to India and China, Iran’s own exports suffered. Both Russia and Belarus are leading exporters of fertilizers, nixing the market for potash, a key Belarusian export. And while Russia’s difficulties with its domestic automobile industry was seen as an opening for Iran’s efforts to export vehicles and parts, the woeful safety record and reputation of Iranian vehicles cast doubt on the success of any arrangement.

Likewise, while Tehran reportedly agreed in August to supply Russia with aircraft parts in an effort to thwart sanctions, and Moscow last year reached an understanding with Tehran to export Russian aircraft to Iran, the viability of such dealings is questionable.

“People in Russia don’t want to drive Iranian cars, and people in Iran don’t want to fly on Russian planes,” said Piatetsky.

More To Come

Nevertheless, officials from both Russia and Iran appear committed to continuing to look for new trading opportunities among states interested in helping them fight what they believe are Western efforts to isolate them economically.

Russian President Vladimir Putin pledged on December 15 that his country would continue its efforts to boost trade with partners in Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

“We will never take the route of self-isolation,” Putin vowed. “On the contrary, we are broadening, and will broaden, cooperation with all who have interest.”

But ultimately, most of the dealings among sanctioned states are relatively small-scale, and experts see serious limits to what Russia and Iran and their disparate crew of trading partners can do to effectively counter the punitive measures against them.

“These sanctions-circumvention measures…may ensure regime survival, but will not lead to economic growth,” said Tsai. “It is inconceivable that this ‘bloc’ of sanctioned nations will rival the West economically in any way.” (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty)