By Rifat Latifi, MD, FACS, FICS, FKCS***

The essay appeared first at the Kosova Journal of Surgery a publication of Kosova College of Surgeons

PERSPECTIVE

Abstract

Being the Minister of Health, of any country, is the greatest honor and privilege, but being the Minister of Health in Kosova, the newest country in Europe and where I grew up and was educated before I left for a better life, is a very different honor yet is the biggest responsibility that I could have. As a surgeon, I have worked hard to prepare for any occasion and to treat any condition in my domain. But, how does one prepare to be the Minister of Health? What tools does one need to have that can help the Minister transform a healthcare system in disarray? How much money do you need? How do you fight the corruption embedded in every layer of the healthcare system? Can you use medical diplomacy as a potential tool to deal with the problems of inequality and healthcare disparity?

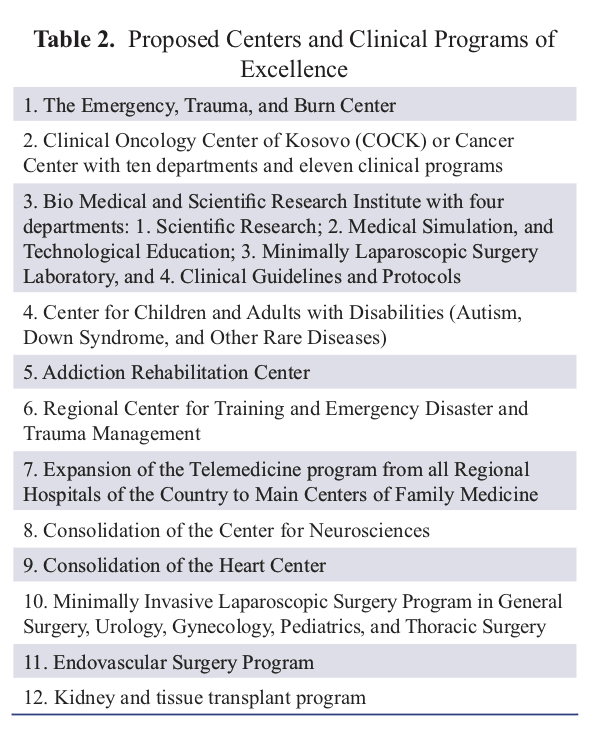

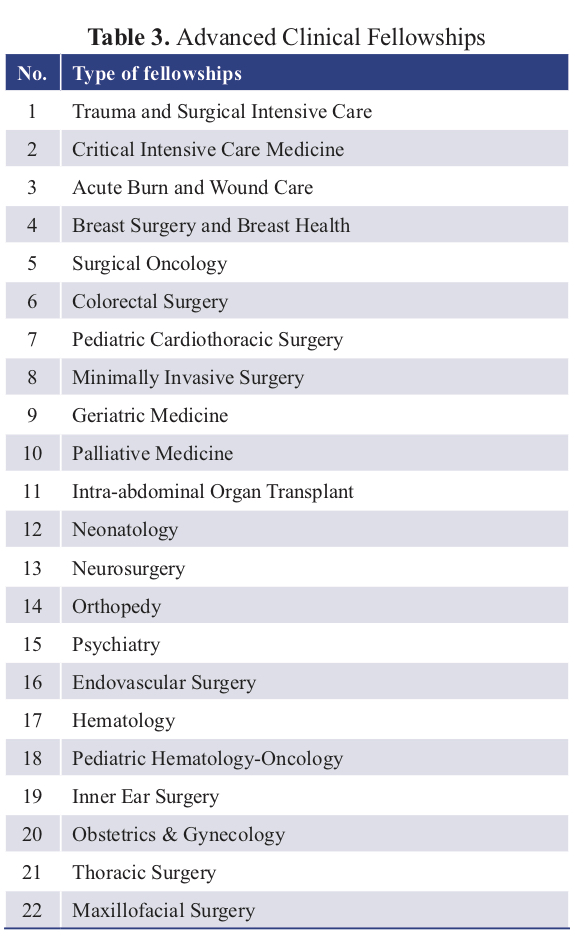

In this perspective, I will discuss my short tenure as Minister of Health in Kosova and how, during that time, we created a model of healthcare transformation in Kosova, using every possible tool, including international medical diplomacy. We designed a two-prong process: 1) creating 12 clinical centers and programs of excellence (CCE), 22 advanced clinical training fellowships (ACTF) for more than 100 physicians and surgeons (during 2022–2024) at international centers of excellence, while simultaneously starting to reform residency training programs and building research capacity and infrastructure, and 2) working through local and international collaboration in order to build and modernize the hospital infrastructure, and improving the quality of healthcare services, and management skills. This was an ambitious plan, one has to agree, but these measures were the only way to transform the healthcare system and reduce patient flow outside of the country and public healthcare institutions. We knew that transformation would not happen quickly. It would take time, but we needed to start with a comprehensive plan and vision.

Transformation From Chairman of Surgery to the Minister of Health

On November 16, 2022, at the invitation of Prime Minister Albin Kurti, I took over the job as the Minister of Health in Kosova, a non-political Minister. While it was never something I had imagined doing in my career, I was not surprised by my own willingness to accept this position. A lifetime opportunity. I thought, finally, I can help transform healthcare in Kosova. Yet, I had a few questions: Was I prepared to be a Minister? Could not find a book on how to become a good Minister. What will it be like? Will I have the needed support?

Following graduation from Medical Faculty of University of Prishtina and two years of residency in orthopedics, I moved to the USA in 1985. Since then, I have trained and worked in major medical institutions in the USA (Houston, Texas, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Cleveland, Ohio, New Haven, Connecticut, Richmond, Virginia, Tucson, Arizona, Valhalla, New York) and abroad (Doha, Qatar) and led a major academic department of one of the oldest university hospitals and medical schools in the USA (Valhalla, NY). I have written and edited 20 books, including one entitled “Modern Hospital”. In addition, I have published more than four hundred peer-reviewed articles and book chapters. I am familiar with the healthcare system in Kosova and have also critiqued how healthcare was being managed during the last 2–3 decades. As the founding president of Kosova College of Surgeons (KCS), I led the creation of daily operations and content, as well as the growth strategy of KCS. Should all this have prepared me for a job as the Minister? My answer was yes. It made perfect sense to me, then and now, to leave my position at NYMC and WMC in Valhalla, NY (even though it was abrupt, surgically one can say) and come back to Kosova to help rebuild the healthcare system. Most importantly, at this stage of my career (been there, done that), I thought I could help Kosova. So, I said yes to the invitation by Prime Minister Kurti and abruptly left my job as chairman and director of surgery in Valhalla, New York. Normally, one would have to give at least six months’ notice in advance, but instead it was one phone call to Gary Brudnicki and Mike Israel, my bosses at WMC, the day before I travelled for Kosova. Both were surprised (as I was), but incredibly supportive and understood the gravity of my decision. The news went viral. Many were surprised, some were supportive, and others thought -it was a bad idea.

I came in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, while I was creating the cabinet and learning an administrative maze. I was welcomed by the protests of residents and nursing staff in front of my office at the Ministry of Health (previously an old tuberculosis hospital), where, as medical student, I did the rotation on pulmonology. Media outlets had a lot to say about my cowboy boots and bow tie. None were interested in my vision to transform the healthcare system.

As the new Minister, I met many new people, ambassadors of many countries, many representatives of various governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and partners of the Ministry of Health, both national and international. I particularly enjoyed parliamentarian meetings. Having members of parliament express themselves freely, criticizing ministers and the Prime Minister was not allowed just 25 years ago. Now, we are a democratic nation with our own parliament. I love democracy. What else can one want?

My calendar was terribly busy, but I enjoyed. I woke up at 5 AM, and was usually emailing my team by 5:15. There were way too many useless emails, and when I did reply, I was told that I was the only minister that sends emails. There were to many of these meetings too, courtesy dinners, lunches, and other useless meetings. When do you actually work? I kept asking. Five to eight AM. I would answer myself. I lived alone in my apartment (first few months) in the most famous, muddy, and always under construction, “Muharrem Fejza” street. I often did not have electricity and had to walk to the 8th floor to get to my apartment. I did not mind the walk at all. The apartment was small (compared to my house on the hill in Katonah), and the winter was brutal. My apartment was cold too, and I do not like the cold. My life became a mess, but I loved my new mission. Days were passing and I remained very busy, but I could not see as much satisfactory progress as I expected. As a surgeon, you see progress immediately. Not as the Minister.

The State of Healthcare in Kosova

It did not take long to conclude that the healthcare sector in Kosova, particularly the administrative part of the Ministry itself, was a very complex enterprise: a maze or web of entanglement in incomprehensible designed rules, regulations, and policies in which many actors had stakes. The healthcare in Kosova was ignored for decades, if not outrightly neglected, poorly managed, segmented into ridiculous segments and clinics that had more doctors than beds: clinics with no professors, but many directors. There were many questions that I could not get answered. Why was Kosova healthcare sector in this state? A state of disarray. Why did the public healthcare system continue to be underfunded year after year, government after government? Why did Kosova have the lowest GDP for healthcare in the Western Balkans countries and amongst the lowest in the world? Why, even when something was invested, was it mismanaged? Why were so many hospitals started but were never finished? A hospital donated and inaugurated but had no patients? The hospital infrastructure is old, or of low quality, and for many years, there have been a number of hospital buildings (such as emergency and trauma hospital building, the Ferizaj regional hospital building, the pediatrics department at Mitrovica hospital and a few other projects) that have remained unfinished or not completed for various reasons; they look like ghost buildings that have disintegrated year after year. The central pharmacy of UCCK is placed in a malodourous and poorly secured basement of Genecology and Obstetrics clinic. Why did private “hospitals”, private clinics, and pharmacies grow like mushrooms right in the backyard of the public University Clinical Center of Kosova? Who owned them? It is difficult to understand the web of manipulation and outright abuse of the public trust and healthcare system, the very same healthcare system that should care for all of us, rich and poor. Due to low wages, most physicians, nurses, laboratory technicians, and others healthcare workers are forced to work 3–4 jobs, often to the detriment of public hospitals. All doctors work without malpractice insurance, because no one has ever asked for it, despite the fact that court cases often get dragged out for years in courts, fuelled by the media with unverified information. Clinical faculty were divided into those who teach medical students at the Medical Faculty of University of Prishtina and those who “cannot”. For both groups (although many are Doctors of Science or have Master’s degrees), the scientific contribution and peer-reviewed publications are very low.

Answers to all these questions were not easy to find. That is how it is here in Kosova, everyone was telling me. Matter fact. I could not understand, and it was impossible to justify this state of the healthcare system. How does an ordinary mind understand this? In asking this question, I found solace in working on a new complex and ambitious transformation plan. Study after study of many donors and partners came to the same conclusions: Kosova has too many hospital beds but an occupancy rate of just about 50%, too many doctors (most of them in Prishtina), too many nurses, no efficiency, and a major mismanagement of resources.

How can 15 surgeons perform only 1,500 operations per year or, even worse, 13 surgeons perform only 600 operations per year and, in both cases, the majority of procedures not be major surgeries by any standard?

The answers were a lack of available operating rooms (OR), a lack of anaesthesiologists, a lack of OR nurses, and other managerial issues. The University Clinical center has 37 operative rooms that are dedicated ORs for certain clinical disciplines. I could not help but remember that Westchester Medical Center where I was a director of surgery had only 21 ORs (7 of which were ambulatory ORs), where we did everything including heart and liver transplants and everything in between, in all clinical disciplines. When one needed an OR, the one that was not busy became your OR.

Over the span of 23 years since the war ended, despite the lowest GDP share, large amounts of funding from international donors and various NGOs have come to the healthcare system. Several Ministers, governments, and directors of hospitals and clinics have come and gone, but the situation has not changed. Even when highly expensive medical equipment was purchased, they did not function, another mystery to me.

Visiting the various departments and clinics reminded me of days when I was a medical student here: four patients in one room. Even in the renovated parts of the hospitals that have been finished in the last few years, there are three beds in one room (for the most part); the offices of staff occupy large portions of hospital wings, with one exception, the new pediatrics wing of surgery.

In summary, the public healthcare system in Kosova has remained in disarray and, overall, can be realistically characterized as unsafe, unregulated, low quality clinical services with a lack of clinical faculty ability and skills, modern hospital infrastructure, and, above all, lack of managerial skills at all levels. Most patients with complex diagnoses are sent out of the country or private institutions for treatment, at an astronomical cost.

How Do We Transform the Healthcare In Kosova? – A Trauma Surgeon’s View

Can we transform healthcare in Kosova? I asked myself every day while the Minister and still do, now one month after I have resigned from the position. Rightly, people of Kosova asked the same question.

Yes, we can, is my unequivocal answer, but it will require support for the vision and new investments, determination, and time. But, how do you transform this state of healthcare and deal with each of these parts and segments of this very complex and distorted mosaic and healthcare disparity? The ugly truth of the healthcare system is that those who have the financial means go to boutique private hospitals and clinics in the country or outside. Most rich people use Germany, Turkey, and other countries for routine examinations. Most politicians go to private hospitals or outside the country even for routine procedures. Those who do not have the financial means or do not have any one in the hospitals to vouch for them are faced with long wait times to see a doctor, with even longer wait times for a radiologic test or procedures or even an operation unless it is an emergency. These wait lists are often super-inflated and are created by some doctors in order to have patients go to private institutions to see the same doctors. Not all doctors are like this, but a majority are. It should not be like this. But it is here, and we must deal with it. Let me try to simplify the answer to can we transform healthcare in Kosova, using the analogy of a trauma surgeon. As trauma surgeons, we save many lives by stopping the bleeding, securing the airway (intubate the patient early), always expecting the worse, performing laparotomies or emergency thoracotomies or whatever it takes, and working system by system, organ by organ, and simultaneously using lots of blood and blood products.

In rebuilding the healthcare system, we must use the same approach. Stop the bleeding (stop the flow of patients out of the country). This can be done by creating local expertise and modernizing the hospital infrastructure. Secure the airway (bring oxygen for the healthcare system) by adding resources to provide high-quality healthcare services and curbing treatment abroad, and finally, transfuse blood (transfuse knowledge and reform training ) to increase the ability to make the provision of high-quality services possible.

In summary, to achieve this, however, there are a few (essential) requirements: 1) Attract well-trained and prepared medical students, residents and fellows, faculty, nurses, and healthcare managers; 2) Modernize the hospital infrastructure, by putting in place an advanced internationally- accredited healthcare system with health insurance and a health information system, and finally, 3) Exhibiting professionalism and dedication at all levels by each and every one of us. People of our small but beautiful country deserve that. They fought for this; they expected this from us, and we have failed them. The question remains, how do we do all this and is there an appetite for change?

The Medical Diplomacy and Data Driven Strategy as Tools of Transformation

The backbone of medical diplomacy or global health diplomacy (GHD) has been defined as wide spectrum of health determinants as a crucial element in foreign, security, and trade policy, and require collective action1, 2, 3. Efforts in global health diplomacy have been broken down into seven concepts 4,5 that include: 1) Promoting healthcare in the face of other interests; 2) Establishing new governance mechanisms in support of health; 3) Creating alliances in support of health outcomes; 4) Building and managing donor and stakeholder relations; 5) Responding to public health crises in a timely fashion and with appropriate tools and means; 6) Improving relations between countries through healthcare relations; and 7) Contributing to peace and security between nations and people by a variety of means. Which one of these dimensions can a country, region6, special group of scientists7 or continent8 find most suitable is a matter of creativity or political will and establishment.

Medical diplomacy has been shown to be a great tool to create bridges between nations and countries as well as institutions, and for establishing infrastructural, administrative, and regulatory support9 .

Moreover, medical diplomacy has taken a center stage as an emerging field that bridges the disciplines of public health, international affairs, management, law, and economics10, 11. The question still remains, who should be involved in medical diplomacy? Should diplomatic core be better prepared for health diplomacy and for fostering effective global health action that aligns public health and foreign diplomacy outcomes11. My answer is yes they should but medical diplomacy is everyone’s business, but Ministers of Health should lead the process based on their country’s needs and global interest while working very closely with other segments of the governments (the Foreign Affairs Ministry and the entire diplomatic core).

With all this in mind, I embarked on medical diplomacy, starting with Albania; visited several countries including the USA, Turkey, Norway, Greece, Austria; and was in the process of establishing relationships with a number of other countries including Luxembourg, Croatia, Slovenia, Saudi Arabia, United Arabic Emirates, Qatar, Israel, Slovakia, Germany, Australia, India, and others to ensure that our physicians got training and expertise. Each and every one of these countries were happy to help Kosova’s healthcare transformation, but the narrow-minded media and some politicians sadly did not see it that way. Building international relationships to support the needs of the healthcare system in Kosova is the only way to bring the much-needed resources, education, and training opportunities to the country and medical personnel. Over last three decades we relied on teaching each other. It is like the blind leading the blind. We were blinded to science and modern medicine for the last 30 years. Overcoming these embedded consequences of three decades will take time and data, as real transformation cannot happen without data. There is no other way!

Methodology and Analysis of the Current State

During the months I was in the office , my team and I performed an analysis of the healthcare system, using the following methodology: 1) Interviews with various stakeholders, and a written survey for key clinical leaders (directors of each clinical discipline); 2) A review of all patients treated outside of the public healthcare system, including the total number, diagnosis, reasons for treatment abroad (2019-August 2022); 3) Review of all reports of costly consultants on hospital infrastructure; and other opinions and materials available to the Ministry of Health in Kosova (MHK) on infrastructure, hospital bed occupancy, human capacities, and healthcare efficiency.

Results – Seven pillars of transformation

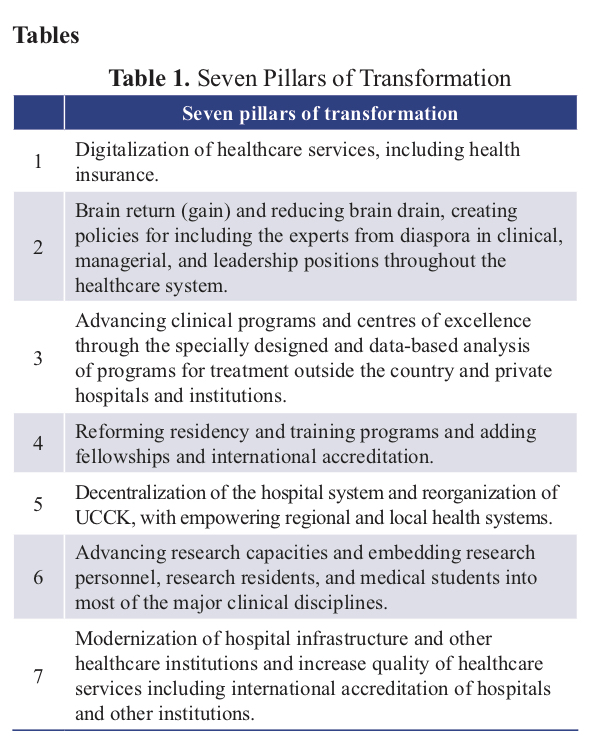

The main outcome of this analysis was the lack of clinical expertise, hospital infrastructure (equipment or technology), lack of system in place ( trauma and emergency system) or others factors (lack of legislation for transplant), which lead that great number patients with even trivial problems (need for biopsy) to be sent out of the country for treatment. The cost for each organized and highly structured enterprise was tremendous, and the amount for each patient that Kosova paid or owe to many countries, with the majority (84%) owed to Turkish private hospitals was incredible. Based on these analysis and reports we designed a seven point (or pillar) platform from which the entire strategy of transformation will be derived (Table 1), that will include centers of excellence (Table 2) and establishing new advance clinical fellowships (Table 3).

Transformation of Residency and Adding Fellowship Training Programs

Ordinarily, the transformation of a healthcare system start with medical school and with residency programs, and not with fellowships but Kosova does not have time. In fact, for the transformation of the healthcare system, Kosova has everything but time. It needs a mechanism to prepare the residents and trainees in post-graduate residency training or fellowships, so they can help training residents and new fellows of the future. To achieve this, we designed a plan to train more than 100 physicians and surgeons during 2022–2024 in international centers of excellence and 22 clinical disciplines, including 2–6 fellowships in each clinical field (Table 3). In other words, the residency and fellowship training programs will need to undergo significant reform.

Residency and fellowships programs should enroll new residents and fellows on an annual basis for most clinical programs— based on clinical needs for the country and international standards and accreditation.

There has never been a study on long-term needs of healthcare in Kosova. The residency training programs in anaesthesiology and critical care, general medicine, primary care, family medicine, public health and epidemiology, and other deficient services will be promoted. Moreover, each potential resident will have to serve as a general practitioner for a minimum of two years before entering residency, while the internship will be structured in a particular specialty and will last one year. The fellowships training programs or subspecialty training programs need to be structured and accredited internationally, while adding structure and administrative professional support to residency and training programs. The fellowships will be well- structured and have a well-designed curriculum with partner countries and institutions. It is predicted that the initial educational cost of these fellowships will only be around three million Euros, but these expenses will be offset by significantly curbing the flow of patients seeking treatment out of the country. Simultaneously, hospital infrastructure and medical equipment will be needed while education is undergoing.

Another, critical element of transformation has to do with advancing human abilities and modernization of training programs, with the addition of research experience for residents and trainees. This should be done by adding 1–2 years of mandatory research training before or during residency programs; combining research programs with MPH, Doctor of Science, or Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) programs; collaborating with the medical and pharmaceutical industry; and embedding clinical scientists in each clinical discipline as part of the research staff.

Summary

The main objective and goals of transformation of healthcare of Kosova are to advance clinical medicine and surgery, increasing human abilities and expertise; reduce the number of patients flowing outside of the country or to the poorly regulated private sector to zero; and deepen the relationships between Kosova and partner countries. This should not be a medical neo- colonialism, as it has been thus far, for the most part.

It should be a true partnership built through medical diplomacy and friendship, aiming for Kosova to become part of the global medical village and to independently run its medical affairs. This totally can be done, but Kosova needs to lead the process, not those who benefit greatly from our medical incompetence. Finally, the next leaders of healthcare in Kosova will need to have the expertise and knowledge of how to do it but mostly free hands to transform and lead the change.

Despite a great deal of difficulties at each step from the moment I took over my tenure as Minister of Health in Kosova, we have made significant progress. We have a clear picture what is missing. Moreover, we have defined the platform and the path to transformation by creating seven pillars of transformation, establishing 12 centers of excellence, and 22 advance clinical fellowships and reforming the residency training program. All these steps will improve human capacities and the hospital infrastructure and this will stop or significantly reduce treatment abroad.

I still believe that, while the odyssey of transformation is complex in any circumstance, and despite many distractions, obstructions along the way from the incompetent and corrupt administration (that must be changed) and corruption on many levels of healthcare system, Kosova’s healthcare can prosper and become independent. Let us remember that there is no true country independence without healthcare independence. Only then will young people see that they can achieve their full potential and see the opportunities I see for them in the future, right here in Kosova. But, it will take time and real dedication from the government and confidence and knowledge to trailblaze these changes. The first step though is to admit that the Kosova healthcare system is in disarray.

Personal Note

On a personal note, this has been one of the most remarkable segments and truly enriching experiences of my life. It has been an awesome opportunity to attempt to give back all I know and have learned in the USA and around the world, as well to attempt to integrate that global experience into our vision and mission of healthcare transformation in Kosova. We cannot accomplish this major transformation without partnering with countries around the world and without using medical diplomacy as a platform. Finally, my heartfelt thanks to Prime Minister Kurti for the lifetime opportunity to serve people of Kosova, and to all my friends, colleagues, my fellow ministers and other government personnel, members of parliament, and all those who helped me during my tenure. In particular I want to thank my cabinet members Kujtim Salihu, Liridon Iberdemaj, Lumturije Bekaj, Anton Shllaku, Lumnije Kqiku-Biblekaj, Arsim Berisha, Valon Baraliu, Kujtim Shala and my family for their unconditional dedication to changing the healthcare in Kosova during difficult times, and to Kalterina Latifi for her insightful editorial comments during the preparation of this work.

REFERENCES

1. Kickbusch, I., & Liu, A. (2022). Global health diplomacy-reconstructing power and governance. Lancet, 399(10341), 2156-2166. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00583-9.

2. World Health Organization. (2020, August 18). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—Aug 18, 2020. Retrieved September 10,2022) from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—18-august-2020

3. Maurice J. (2015) Expert panel slams WHO’s poor showing against Ebola. Lancet;386(9990):e1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61253-3.

4. Kickbusch I, Nikogosian H, Kazatchkine M, Kökény M. (2021). A guide to global health diplomacy. Better health—improved global solidarity—more equity. Retrieved from: https://www.graduateinstitute.ch/sites/internet/files/2021-02/GHC-Guide.pdf

5. WHO (20220. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/news/african-island-states-launch-joint-medicines-procurement-initiative) (accessed on September 6, 2022).

6. Bonilla K, Cabrera J, Calles-Minero C, Torres-Atencio I, Aquino K, Renderos D, Alonzo M. (2021 Jul 12) Participation in Communities of Women Scientists in Central America: Implications From the Science Diplomacy Perspective. Front Res MetrAnal.6:661508. doi: 10.3389/frma.2021.661508. PMID: 34368614;PMCID: PMC8344979;

7. Soler MG (2021 Jun 17). Science Diplomacy in Latin America and the Caribbean: Current Landscape, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Front Res Metr Anal.6:670001. doi: 10.3389/frma.2021.670001. PMID: 34222772; PMCID: PMC8247908.

8. Chattu VK, Dave VB, Reddy KS, Singh B, Sahiledengle B, Heyi DZ, Nattey C, Atlaw D, Jackson K, El-Khatib Z, Eltom AA. (2021 Nov 9). Advancing African Medicines Agency through Global Health Diplomacy for an Equitable Pan-African Universal Health Coverage: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health.18(22):11758. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182211758. PMID: 3483151

9. Brown MDM, Tim K, Shapiro CN, Kolker J, Novotny TE (2014). Bridging Public Health and Foreign Affairs: The Tradecraft of Global Health Diplomacy and the Role of Health Attachés. Sci Diplomacy. 3:3.;

10. Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, Reddy KS, Rodriguez MH, Sewankambo NK, Wasserheit JN (2009). Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet. 373(9679):1993–1995. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60332-9.

11. Brown MD, Bergmann JN, Novotny TE, Mackey TK (2018 Jan 11). Applied global health diplomacy: profile of health diplomats accredited to the UNITED STATES and foreign governments. Global Health.14(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12992-017-0316-7. (https://ysph.yale.edu/news-article/neocolonialism-and-global-health-outcomes-a-troubled-history/) (accessed 09-05-2022).