Her metaphoric, metamorphic imagination roils the poems to an intensity that the tone keeps pressing back down

By Rosanna Warren

Ani Gjika has managed a feat of tact in these poems recalling a harsh childhood in Albania and a peripatetic life that has taken her to India, Thailand, and to citizenship in the United States. Other poems in the book delicately register the ebb and flow of feelings in a marriage, with equal tact. In the Communist Albania evoked here, danger looms: from hunger, cold, political surveillance, the threat of execution. Quietly the child’s perceptions inflect the adult poems. Just as quietly the poems of adult life, anxiety, and loss keep their balance.

“Inarticulate,” which opens the collection, presents a scene of people getting off a bus in a mountain valley to drink from a stream: “I never dream of it/but I remember being watched/ as I stood at the edge of the water/ stirring images with my foot.” As the poems progress and expand this portrait of the recollected world, the sense of being watched grows more sinister: “Each family eavesdropped on the next like clockwork,” we learn from “White Noise.” But the most powerful watcher here is the poet herself: the child who observed, the grown woman who remembers and records.

Gjika has turned English, her adopted language, into a subtle instrument, a beautifully judged voicing that never slides into self-pity or melodrama, never loses its cool. It is an achievement in which ethics cannot be distinguished from poetic style. The justness of Gjika’s phrasing has everything to do with her exact and trustworthy weighing of justice, the unspoken norms of decency that stand, immensely implied, in the background of these poems whether set in or out of Albania. In “The Winter of my Childhood,” one of the key poems of the book, the child draws stars while “Politics on TV scratched at the screen,” and freezing weather menaces the family:

That year winter threatened our small house.

I heard winds howl, but I had drawn enough stars

to burn in the stove to keep us warm.

With similar reticence, in “White Noise,” a poem mostly concerned with details of domestic life, a one-line stanza coolly declares, “Nobody I loved was taken into the woods and shot.”

In “Inarticulate,” Gjika showed us a snapshot of herself as a child at the edge of water, “stirring images with my foot.” She stirs images throughout these pages; her metaphoric, metamorphic imagination roils the poems to an intensity that the tone keeps pressing back down. That conflict gives her art its essential charge. Her world is animate, almost Ovidian. Watch these transformations: “I believe a river caught up with us” (“Inarticulate”). “India runs away the moment I arrive,” and “Drums so loud/ they beat a god inside me” (“Last Day,” from “India: Three Poems). “It’s raining again, a chain stitch/ unraveling on my windshield/ a form of writing you understand” (“Passageway”). Her diction and syntax are clear and direct, an almost transparent medium in which images and story are revealed, “developed” like photographic film in the darkroom.

The subject matter taking shape here is often violent or sensual, or both. In one of the Albanian poems, children “…awoke in spring, our bodies// overgrown with weeds. Our parents/ had no idea how to save us” (“The Winter of my Childhood”). In “Children Story,” a retarded boy named Çimi who has been abandoned by his mother and eats ants sets a cat on fire with gasoline and watches “the mad cat dance.” Girls sneak into their mother’s bedroom, borrow her necklaces, and slide them over their vaginas: “What the older one keeps thinking of/ is their mother wearing these necklaces/ afterwards—the smell of her sex/ rising and falling on a woman’s chest” (“Little Women”).

Gjika carries these virtues of clarity and startling imagination into the poems set in other countries and in adult life. The third section, “Portrait of a Couple on the Grass,” takes its title from her poem inspired by a photograph of George and Mary Oppen in which the balance observed between the man and wife in the picture (“so that one’s weight never cancels the other’s”) seems an ars poetica for Gjika’s own work. The Oppens in “Portrait of a Couple on the Grass” and Vallejo and his unnamed bride-wife-widow in the poem “His Wife” create a context for the scenes of the poet’s marriage under the stress of the husband’s unemployment, depicted here with affection, sorrow, perturbation, and stoic calm. In the charged atmosphere Gjika has created, each simple object acquires the force of symbol with no explanatory intervention. On the unemployed husband’s neat desk, this poignant printed statement accompanies a recent battery order: “no special instructions necessary/ for rebuilding”—in a life that urgently requires rebuilding.

Ani Gjika’s book follows a gentle narrative arc from her Albanian childhood, her life in India and Thailand, to accommodation to life with all its immigrant difficulties in the New England. It is also a life in her adopted poetic language, in which the sound of a commuter train becomes a promise of composition and integration: “Whistles weeeeeave weave weeeeave…” (“Location”). She has made this language her own in poems beautifully woven in a design of great depth of feeling and intelligence.

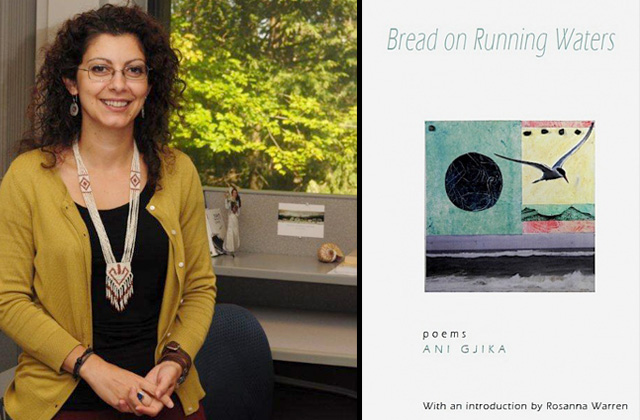

Fenway Press is delighted to publish Ani Gjika’s first book of poems, BREAD ON RUNNING WATERS.

Born and raised in Albania, ANI GJIKA moved to the U.S. at age 18 and studied poetry writing at Simmons College and Boston University. She is the recipient of a 2010 Robert Pinsky Global Fellowship and winner of a 2010 Robert Fitzgerald Translation Prize. Her first book, Bread on Running Waters, was a finalist for the 2011 Anthony Hecht Poetry Prize and 2011 May Sarton New Hampshire Book Prize. She is working on an anthology of poetry in translation by Albanian women.