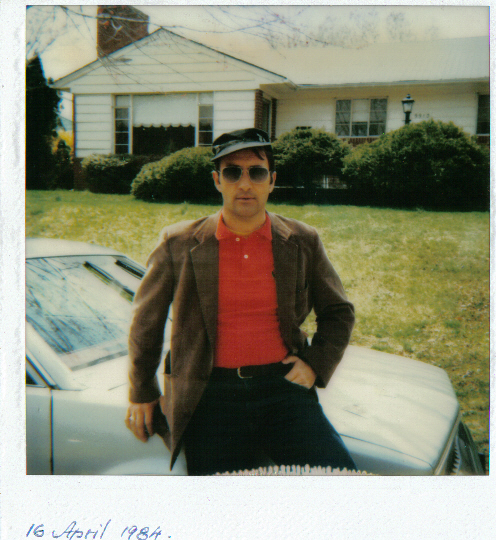

Iva Gjoni

He climbed the barbed wires on an August night. His goal was to be on the other side of the Albanian border, away from the communist siege, toward the free world…toward America. It was the 80’s. The closing, the absence of freedom, and poverty were unbearable. So he left. Three thousand shots were fired. They say he was wounded. The soldiers found photographs dropped during the escape – photographs of his daughter, his wife, his mother. But he left and the Albanian court sentenced him in absence to prison or perhaps death. He was named “the enemy of the people” (no, no it is not Ibsen’s drama!). He searched for freedom, crossed over the wires and left behind the terror of the dictatorship and slavery that so many had to endure with no possibility to ever see the light of freedom.

But freedom has a high price. Any kind of outside connection was forbidden by the Albanian government – not one phone call, no news at all. How is his daughter? His mother? His sisters? He doesn’t know. Albania has its doors closed. His family is exiled. Who would dare to write a few sentences to him? Who would dare to send any kind of news?

Thus desperation killed you slowly. The free world, so pretty and so much desired could not be enjoyed. Those who escaped Albania at that time were isolated and alone. They had lost all hopes to see their families ever again. Every stone of the motherland became precious. Ah, if it were only free! Ah, if their motherland were free!

This is the story of an immigrant who lived and died in New York. His pain was too strong. He loved freedom more than anything else but his love for his family could not be replaced. This is Noli’s, Koliqi’s, Shiroka’s tragedy; the tragedy of all those who left Albania in search of freedom, of those who died of pain and yearning for the motherland, who hoped to see it free – this is the tragedy in search of freedom.

A poem dedicated to his mother by Vasil Gjoni:

To my mother, Eftali

Will the voice of that gloomy muse

reach your ears?

Will your serene soul learn

what my heart feels?

Or like lost love

will this call disappear

without waking in your soul

memories so dear?

Listen, at least, to the sounds

for which you perhaps wait

and know that in my solitude

in my troubled fate

your last words “Vaso, come back!”

that you whispered as I depart

Remain sacred and are treasured

and are love for my heart.

A few memories written in letters (correspondence) by Vasil Gjoni:

Letter #1: written by Vasil Gjoni on March 24, 1985, New York

Honorable Sir H. and Sir H.:

I wish that my letter finds you well. An old Albanian proverb says, “Life is more important than anything else.” It has been twenty months since the day I left my motherland. I lived for about six months in Yugoslavia … and on January 19, 1984 I arrived in Silver Spring, Maryland, where my father, Stefan Gjoni, lived from 1920-1934 and where he graduated from Georgetown and became a doctor. Later he returned to Albania where he worked in Kukes, Tropoja, Puke, Peqin, Kavaja and, at last, since 1946 in Kruja. He died on October 30, 1981; he was honored and respected by the people of Kruja. On the night of his death, your wife H., together with your sons T., D. and their wives stayed next to his body and the next day, with a mortal ceremony according to Kruja’s rituals, he was taken to his resting place at the cemetery of “Mani i Tupes.”

Your family organized the burial ceremony, welcomed and greeted the guests, and we did as they wished: we left the body in an open cask, his head facing west. Everyone, taking turns, lightly touched his cheek. He was the man who had been able to serve and gain the hearts of the citizens of Kruja for 55 years.

In memoriam, F.K.’s nephew built a wonderful tomb according to my project: a white tomb that shines there day and night, in the place where Stefan had asked to be buried since 1976.

Every night I dream of the mountains, the fields and the people of Albania where I spent 35 years. Every time I climbed to the top of the mountain, from that amazing altar I felt like a bird and wanted to fly and devour all the beauties and marvels of my country from north to south… I live with little hope that one day, perhaps, they will allow me to smile again and to enjoy my family’s love and that of my nine year old daughter, who I left on the other side of the ocean. A great Latin philosopher has said, “We do what we can if we cannot do what we want.” We cannot control what metamorphism, what fate, what kind of life we will experience in the future. As time passes, with its misfortunes and tragedies, it leaves something behind. Progress does bring something new. It is a mystery how long this will last and what will happen in the future. Perhaps the coming years will bring mercy to us and will allow our dream to come true; the dream to see my country one more time, which I have never loved more than I do now, being so far away from it. Every stone, every tree, every house there is part of my life and this is the sorrow that tortures and torments me in my solitude.

I wish that the condemnation of our soul will not last long. Every bad experience has something good in it. Let us wait and see.

Hugs,

Vasil Stefan Gjoni

Letter #2: written by Vasil Gjoni on June 14, 1985

I have wanted to write for a long time but depression and desperation have not allowed me. This constant suffering bothers me; it could be my family’s curse for abandoning them. I hope it is not my mother’s curse because I won’t be able to resist it. I am angry about everything and neither the skyscrapers of Manhattan nor the beautiful nature of Long Island console me.

Since August 11, 1983, when I became illegal to my country, I have not seen a happy day. I have wanted to smile for a long time but my murdered soul does not allow me. Without family in this world the man has no value or personality.

However, I hope that my letter finds you well and in good health. I would like to tell H. about many things but the distance is an obstacle. I hope to meet one day and to satisfy your curiosity. I’d like to talk about my country, its nature that had stored this destiny for me which I now suffer in immigration. In my foggy memory, when I was little, I remember when H. together with the children brought straw from the swamp to weave and later sell while my father would check if the big gate in the courtyard was locked. During religious holidays we all went to the mountain. T. would put me on a donkey to ride because I could not walk and he, using a sports rifle, would shoot owls along the paved road that took us to the altar on the top of the mountain. We were the first to try the dessert. On August 6, 1983 I had my last coffee with N. while my daughter was playing with other children outside. They did not know we would never see each other again.

It was a cold January night in 1965. Someone in the dark called my father for urgent medical help. My mother and we understood that your brother’s wife was having a heart attack. I hid in my bed alone in the room waiting to see what would happen. In half an hour we heard a woman scream and then crying. In the midst of this panic my father said, “She’s gone.” The cruel night had taken that woman. Her youngest daughter was crying inconsolably. Her son, my brother and childhood friend, was crying in my shoulder.

These are some memories from that life which, if it were free, would have been a wonderful life.

I remember four years ago I designed a house for N., which your family built next to the well in the courtyard. As you may know, your second son in 1960 worked with L. and S.H. One night N. went to his friend next to the Buna River planning to escape the country. But that “friend” betrayed him and gave him to the solders instead. The court, taking into consideration that his father (that means you Sir H.) was a political emigrant, sentenced him to thirteen years in prison, which he completed in 1972. Sometimes I would ask him in confidence, “Why did you trust that friend?” He would say, “Ah, dear Vasil, what can you do? This is how the world is! Some people are honest and some are scoundrels.”

These are some details from many memories. Perhaps another time I will tell you more. I now live in N*’s house, who together with her family has helped me a lot. They have found me work and have given me food and a place to live. I will never forget what they have done for me. They are interested in my every step and give me courage.

(Note: *This is Nderim Kupi’s family)

Greetings,

Vasil Stefan Gjoni

I want to conclude with Filip Shiroka’s words from Go, Swallow:

… If I could fly like you

I would come along

and pass by Shkodra, it’s true

The desire to see it is strong.

but … you go … fly there

and please feel my despair.